Vector space¶

using Pkg

Pkg.activate(pwd())

Pkg.instantiate()

Pkg.status()

using Plots

Vector space¶

- A vector space or linear space or linear subspace or subspace $\mathcal{S} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^n$ is a set of vectors in $\mathbb{R}^n$ that are closed under addition and scalar multiplication. In other words, $\mathcal{S}$ must satisfy

- If $\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{S}$, then $\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{S}$.

- If $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{S}$, then $\alpha \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{S}$ for any $\alpha \in \mathbb{R}$.

Or equivalently the set is closed under axpy operation. $\alpha \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{S}$ for all $\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{S}$ and $\alpha \in \mathbb{R}$.

Any vector space must contain the zero vector $\mathbf{0}$ (why?).

Examples of vector space:

- Origin: $\{\mathbf{0}\}$.

- Line passing origin: $\{\alpha \mathbf{x}: \alpha \in \mathbb{R}\}$ for a fixed vector $\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n$.

- Plane passing origin: $\{\alpha_1 \mathbf{x}_1 + \alpha_2 \mathbf{x}_2: \alpha_1, \alpha_2 \in \mathbb{R}\}$ for two fixed vectors $\mathbf{x}_1, \mathbf{x}_2 \in \mathbb{R}^n$.

- Euclidean space: $\mathbb{R}^n$.

Order and dimension. The order of a vector space is simply the length of the vectors in that space. Not to be confused with the dimension of a vector space, which we later define as the maximum number of linearly independent vectors in that space.

Two vector spaces $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ are essentially disjoint or virtually disjoint if the only element in $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2$ is the zero vector $\mathbf{0}$.

x = [1, -2, -2]

α = -3:0.1:3

f = x * α'

plt = plot3d(

f[1, :],

f[2, :],

f[3, :],

title = "A line passing 0 is a subspace",

lw = 2,

legend = false

)

plot!(plt, [0, x[1]], [0, x[2]], [0, x[3]], arrow = true, lw = 5, marker = 5)

x1 = [2, 1, 0]

x2 = [2, 0, 1]

x = -3:3

y = -3:3

# h = a1 * x + a2 * y is linear and has to pass x1, x2

# so [2 1; 2 0] * [a1, a2] = [0, 1]

# [a1, a2] = [2 1; 2 0] \ [0, 1] = [0.5, -1]

h(x, y) = 0.5x - y;

plt = wireframe(x, y, h, title = "A plane passing 0 is a subspace")

plot!(plt, [0, x1[1]], [0, x1[2]], [0, x1[3]],

arrow = true, lw = 5, legend = false, marker = 5)

plot!(plt, [0, x2[1]], [0, x2[2]], [0, x2[3]],

arrow = true, lw = 5, legend = false, marker = 5)

Questions:

- Are the two vector spaces pictured above essentially disjoint?

- Is a line not passing 0 a vector space?

- Is a plane not passing 0 a vector space?

If $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ are two vector spaces of same order, then their intersection $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2$ is a vector space.

Proof: HW3.

If $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ are two vector spaces of same order, then their union $\mathcal{S}_1 \cup \mathcal{S}_2$ is not necessarily a vector space.

Give a counter-example in HW3.

# plane 1

x1 = [2, 1, 0]

x2 = [2, 0, 1]

# plane 2

x3 = [1, 0, 1]

x4 = [0, 1, -1]

x = -3:3

y = -3:3

# h = a1 * x + a2 * y is linear and has to pass x1, x2

# so [2 1; 2 0] * [a1, a2] = [0, 1]

# [a1, a2] = [2 1; 2 0] \ [0, 1] = [0.5, -1]

h(x, y) = 0.5x - y;

# g = b1 * x + b2 * y is linear and has to pass x3, x4

# so [1 0; 0 1] * [b1, b2] = [-1, 0]

# [b1, b2] = [1, -1]

g(x, y) = x - y;

plt = wireframe(x, y, g, title = "Intersection of two subspaces is a subspace")

wireframe!(plt, x, y, h)

Span¶

The span of a set of $\mathbf{x}_1,\ldots,\mathbf{x}_k \in \mathbb{R}^n$, defined as the set of all possible linear combinations of $\mathbf{x}_i$s $$ \text{span} \{\mathbf{x}_1,\ldots,\mathbf{x}_k\} = \left\{\sum_{i=1}^k \alpha_i \mathbf{x}_i: \alpha_i \in \mathbb{R} \right\}, $$ is a vector space in $\mathbb{R}^n$.

Proof: HW3.

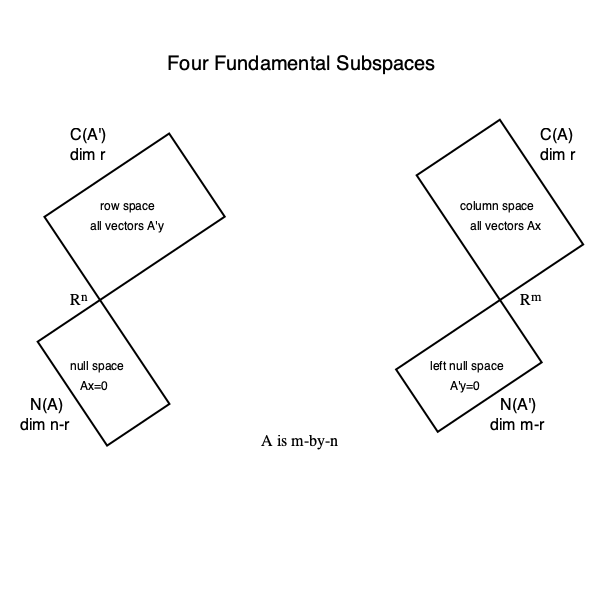

Four fundamental subspaces¶

Let $\mathbf{A}$ be an $m \times n$ matrix \begin{eqnarray*} \mathbf{A} = \begin{pmatrix} \mid & & \mid \\ \mathbf{a}_1 & \ldots & \mathbf{a}_n \\ \mid & & \mid \end{pmatrix}. \end{eqnarray*}

The column space of $\mathbf{A}$ is \begin{eqnarray*} \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) &=& \{ \mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^m: \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} \text{ for some } \mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n \} \\ &=& \text{span}\{\mathbf{a}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{a}_n\}. \end{eqnarray*} Sometimes it is also called the image or range or manifold of $\mathbf{A}$.

The row space of $\mathbf{A}$ is \begin{eqnarray*} \mathcal{R}(\mathbf{A}) &=& \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}') \\ &=& \{ \mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^n: \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{A}' \mathbf{x} \text{ for some } \mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^m \}. \end{eqnarray*}

The null space or kernel of $\mathbf{A}$ is \begin{eqnarray*} \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) = \{\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n: \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0}\}. \end{eqnarray*}

The left null space $\mathbf{A}$ is \begin{eqnarray*} \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}') = \{\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^m: \mathbf{A}' \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0}\}. \end{eqnarray*}

TODO in class: show these 4 sets are vector spaces.

- Example: Draw the four subspaces of matrix $\mathbf{A} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & -2 & -2 \\ 3 & -6 & -6 \end{pmatrix}$. TODO in class.

Effects of matrix multiplication on column/row space¶

$\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{C}) \subseteq \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})$ if and only if $\mathbf{C} = \mathbf{A} \mathbf{B}$ for some matrix $\mathbf{B}$.

In words, right matrix multiplication shrinks the column space.

Proof: The if part is easily verified since each column of $\mathbf{C}$ is a linear combination of columns of $\mathbf{A}$. For the only if part, assuming $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{C}) \subseteq \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})$, each column of $\mathbf{C}$ is a linear combination of columns of $\mathbf{A}$. In other words $\mathbf{c}_j = \mathbf{A} \mathbf{b}_j$ for some $\mathbf{b}_j$. Therefore $\mathbf{C} = \mathbf{A} \mathbf{B}$, where $\mathbf{B}$ has columns $\mathbf{b}_j$.

$\mathcal{R}(\mathbf{C}) \subseteq \mathcal{R}(\mathbf{A})$ if and only if $\mathbf{C} = \mathbf{B} \mathbf{A}$ for some matrix $\mathbf{B}$.

In words, left matrix multiplication shrinks the row space.

Proof: Take transpose of the previous result.

$\mathcal{N}(\mathbf{B}) \subseteq \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A} \mathbf{B})$.

In words, left matrix multiplication expands the null space.

Proof. For any $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{B})$, $\mathbf{A} \mathbf{B} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{A} (\mathbf{B} \mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{A} \mathbf{0} = \mathbf{0}$. Thus $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A} \mathbf{B})$.

Essential disjointness of four fundamental subspaces¶

Row space and null space of a matrix are essentially disjoint. For any matrix $\mathbf{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$, $$ \mathcal{R}(\mathbf{A}) \cap \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) = \{\mathbf{0}_n\}. $$

Proof: If $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{R}(\mathbf{A}) \cap \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})$, then $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{A}' \mathbf{u}$ for some $\mathbf{u}$ and $\mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0}$. Thus $\mathbf{x}' \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{u}' \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{u}' \mathbf{0} = 0$, which implies $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0}$. This shows $\mathcal{R}(\mathbf{A}) \cap \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \subseteq \{\mathbf{0}\}$. The other direction is trivial.

Column space and left null space of a matrix are essentially disjoint. For any matrix $\mathbf{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$, $$ \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \cap \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}') = \{\mathbf{0}_m\}. $$

Proof: Apply above result to $\mathbf{A}'$.

Null space of Gram matrix¶

\begin{eqnarray*} \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}'\mathbf{A}) &=& \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \\ \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}\mathbf{A}') &=& \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}'). \end{eqnarray*}Proof: For the first equation, we note \begin{eqnarray*} & & \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \\ &\Rightarrow& \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0} \\ &\Rightarrow& \mathbf{A}'\mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0} \\ &\Rightarrow& \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}'\mathbf{A}). \end{eqnarray*} This shows $\mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \subseteq \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}'\mathbf{A})$. To show the other direction $\mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \supseteq \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}'\mathbf{A})$, we note \begin{eqnarray*} & & \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}'\mathbf{A}) \\ &\Rightarrow& \mathbf{A}'\mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0} \\ &\Rightarrow& \mathbf{x}' \mathbf{A}' \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} = 0 \\ &\Rightarrow& \|\mathbf{A} \mathbf{x}\|^2 = 0 \\ &\Rightarrow& \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0} \\ &\Rightarrow& \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}). \end{eqnarray*}

For the second equation, we apply the first equation to $\mathbf{B} = \mathbf{A}'$.

Basis of a subspace¶

Eearlier in this class, we talked about basis of $\mathbb{R}^n$. Now we generalize the concept of basis to vector spaces.

A set of linearly independent vectors that span a vector space $\mathcal{S}$ is called a basis of ${\cal S}$.

Let $\mathcal{A} = \{\mathbf{a}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{a}_k\}$ be a basis of a vector space $\mathcal{S}$. Then any vector $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{S}$ can be expressed uniquely as a linear combination of vectors in $\mathcal{A}$.

Proof: Suppose $\mathbf{x}$ can be expressed by two linear combinations $$ \mathbf{x} = \alpha_1 \mathbf{a}_1 + \cdots + \alpha_k \mathbf{a}_k = \beta_1 \mathbf{a}_1 + \cdots + \beta_k \mathbf{a}_k. $$ Then $(\alpha_1 - \beta_1) \mathbf{a}_1 + \cdots + (\alpha_k - \beta_k) \mathbf{a}_k = \mathbf{0}$. Since $\mathbf{a}_i$ are linearly independent, we have $\alpha_i = \beta_i$ for all $i$.

In general, there can be many basis of a vector space. Next result shows that they all have the same number of vectors.

Theorem: Let $\mathcal{A}=\{\mathbf{a}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{a}_k\}$ and $\mathcal{B}=\{\mathbf{b}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{b}_l\}$ be two basis of a vector space $\mathcal{S} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^n$. Then $k = l$.

Proof (optional). Define two matrices $$ \mathbf{A} = \begin{pmatrix} \mid & & \mid \\ \mathbf{a}_1 & \cdots & \mathbf{a}_k \\ \mid & & \mid \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times k}, \quad \mathbf{B} = \begin{pmatrix} \mid & & \mid \\ \mathbf{b}_1 & \cdots & \mathbf{b}_l \\ \mid & & \mid \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times l}. $$ Since $\mathcal{B}$ spans $\mathcal{S}$, $\mathbf{a}_i = \mathbf{B} \mathbf{c}_i$ for some vector $\mathbf{c}_i \in \mathbb{R}^l$ for $i=1,\ldots,k$. Let $$ \mathbf{C} = \begin{pmatrix} \mid & & \mid \\ \mathbf{c}_1 & \ldots & \mathbf{c}_k \\ \mid & & \mid \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{l \times k}. $$ Then $\mathbf{A} = \mathbf{B} \mathbf{C}$. Since $$ \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{C}) \subseteq \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) = \{\mathbf{0}_n\}, $$ the only solution to $\mathbf{C} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0}_l$ is $\mathbf{0}_k$. In other words, the columns of $\mathbf{C}$ are linearly independent. Thus, by the independence-dimension inequality, $\mathbf{C}$ has at least as many rows as columns. That is $k \le l$. Lastly we reverse the role of $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ to obtain $l \le k$.

The dimension of a vector space $\mathcal{S}$, denoted by $\text{dim}(\mathcal{S})$, is defined as

- the number of vectors in any basis of $\mathcal{S}$, or

- the maximmal number of linearly independent vectors in $\mathcal{S}$, or

the minimal number of vectors that span $\mathcal{S}$.

To see the equivalence between 1 and 2. Let $M$ be maximmal number of linearly independent vectors in $\mathcal{S}$. If $\mathbf{a}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{a}_M \in \mathcal{S}$ are linearly independent, then they must span $\mathcal{S}$, otherwise we can add more linearly independent vector(s) to the collection, conflicting with $M$ is the maximmal number of linearly independent vectors in $\mathcal{S}$. Therefore $\mathbf{a}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{a}_M$ is a basis and $M = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S})$.

To see the equivalence between 1 and 3. Let $m$ be the minimal number of vectors that span $\mathcal{S}$. Suppose $\mathbf{a}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{a}_m$ span $\mathcal{S}$ and linearly dependent. Then we can take out one or more $\mathbf{a}_i$ and the remaining vectors still span $\mathcal{S}$. Therefore $\mathbf{a}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{a}_m$ must be linearly independent and thus a basis. Therefore $m = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S})$.

Monotonicity of dimension. If $\mathcal{S}_1 \subseteq \mathcal{S}_2 \subseteq \mathbb{R}^n$ are two vector spaces of same order, then $\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) \le \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2)$.

Proof: Any independent set of vectors in $\mathcal{S}_1$ also live in $\mathcal{S}_2$. Thus the maximal number of independent vectors in $\mathcal{S}_2$ can only be larger or equal to the maximal number of indepedent vectors in $\mathcal{S}_1$.